Culture, International

Earliest evidence for cannabis smoking discovered in ancient tombs

BY

The earliest direct evidence for human consumption of cannabis as a drug has been discovered in a 2,500-year-old cemetery in Central Asia, according to a research paper published today in the journal Science Advances.

While cannabis plants and seeds have been identified at other archaeological sites from the same general region and time period—including a cannabis ‘burial shroud’ discovered in 2016—it’s been unclear in each context whether the versatile plant was used for psychoactive reasons or for other ritual purposes.

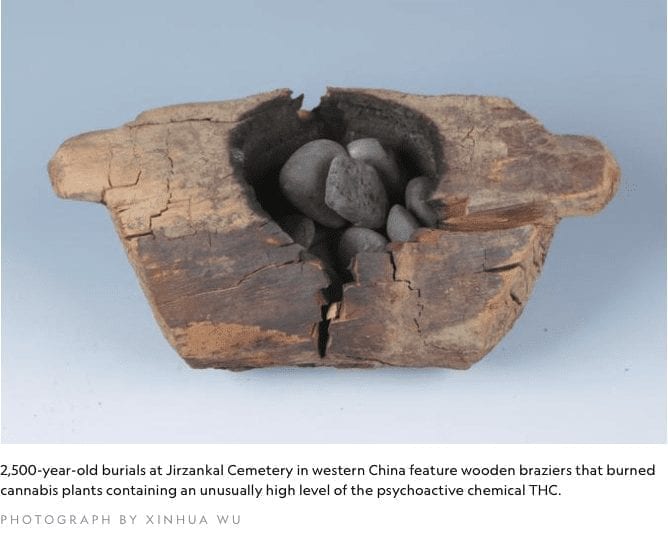

An international team of researchers analyzed the interiors and contents of 10 wooden bowls excavated from burials at Jirzankal Cemetery, a site on the Pamir Plateau in what is now far-western China. The bowls contained small stones that had been exposed to high heat, and archaeologists identified them as braziers for burning incense or other plant matter.

When chemical analysis of the braziers revealed that nine of the ten once contained cannabis, the researchers compared the chemical signature of the samples against those of cannabis plants discovered 1,000 miles to the east at Jiayi Cemetery, in burials dating from the eighth to the sixth century B.C.

They saw that the Jirzankal cannabis had something the Jiayi hemp did not: Molecular remnants of tetrahydrocannabinol, or THC—the chemical responsible for cannabis’ psychoactive effects. The strain of cannabis found at Jiayi does not contain THC, and would have been primarily been used as a source of fiber for clothing and rope, as well as nutrient-rich oilseed.

The Jirzankal cannabis features higher levels of mind-altering compounds than have yet been found at any ancient site, suggesting that people could have been intentionally cultivating certain strains of cannabis for a potent high, or selecting wild plants known to produce that effect.

Cannabis is known for its “plasticity,” or ability for new generations of plants to express different characteristics from earlier generations depending on exposure to environmental factors such as sunlight, temperature, and altitude. Wild strains of cannabis growing at higher altitudes, for instance, can have a higher THC content.

While the researchers are unable to determine the actual origin of the cannabis used in the Jirzankal burials, they suggest that Jirzankal’s elevation some 10,000 feet on the Pamir Plateau may have put people in close proximity to wild strains with higher THC content—or that the cemetery could have been sited at that elevation for ease of access to desirable strains.

Robert Spengler, director of paleoethnobotany laboratories at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History and study co-author, says that the constant stream of people moving across the Pamir Plateau—an important crossroads connecting Central Asia and China with southwest Asia—could have resulted in the hybridization of local cannabis strains with those from other areas. While hybridization is another factor known to increase psychoactive cannabis strains’ THC potency, the question of whether it was intentional, or just by happy accident, is also still unclear.

According to Spengler, this new study demonstrates that already 2,500 years ago, humans were potentially targeting specific plants for their chemical production.

“It’s a wonderful example of how closely intertwined humans are and have been with the biotic world around them, and that they impose evolutionary pressures on the plants around them,” he says.

The discovery at Jirzankal also provides the first direct evidence that humans inhaled combusted cannabis plants in order to obtain its psychoactive effects. No evidence of smoking pipes or similar apparatus has been found in Asia before contact with the New World in the modern era, but the inhalation of cannabis smoke from a heat source is described by the fifth-century B.C. Greek historian Herodotus, who described in his Histories how the Scythians, a nomadic tribe living on the Caspian Steppe, purified themselves with cannabis smoke after burying their dead: “The Scythians then take the seed of this hemp and, crawling in under the mats, throw it on the red-hot stones, where it smolders and sends forth such fumes that no Greek vapor-bath could surpass it. The Scythians howl in their joy at the vapor-bath.”

Herodotus also notes that the cannabis plant “grows both of itself and having been sown,” which University of North Carolina classics expert Emily Baragwanath says is usually interpreted as meaning the plant was cultivated—lending credence to the researcher’s ideas about purposeful cannabis hybridization.

“People have been skeptical of Herodotus’ ethnographies of foreign peoples,” she adds, “but as archaeology looks closer, it keeps finding affinities between the real world and what’s in the Histories.”

Mark Merlin, an ethnobotanist and cannabis historian at the University of Hawaii at Manoa, says the wide diversity in cannabis around the world today is a testament to how long people have been involved with the plant and harnessed its many uses. “It’s a real indication of how long humans have been manipulating cannabis,” he says.

Read more from the source: NationalGeographic.com