By Emily Dufton, American Historical Association

I remember the first time I saw them. I was in the Library of Congress, looking through old issues of High Times magazine. The advertisements for certain products—like the BuzzBee Frisbee (with a special pipe so you could literally “puff, puff, pass”), “You’re the Dealer!” board game, and pictures of clowns hawking rolling papers—seemed both charmingly representative of the mid-1970s as well as pretty blatant in their appeal to kids. The ads also spoke to the enormous paraphernalia market that had risen as a result of a dozen states decriminalizing the possession of up to an ounce of marijuana between 1973 and 1978. The numerous ads that lined the pages of High Times (as well as the existence of the magazine itself) give some insight into just how vast the marketplace, and its clientele, was at the time.

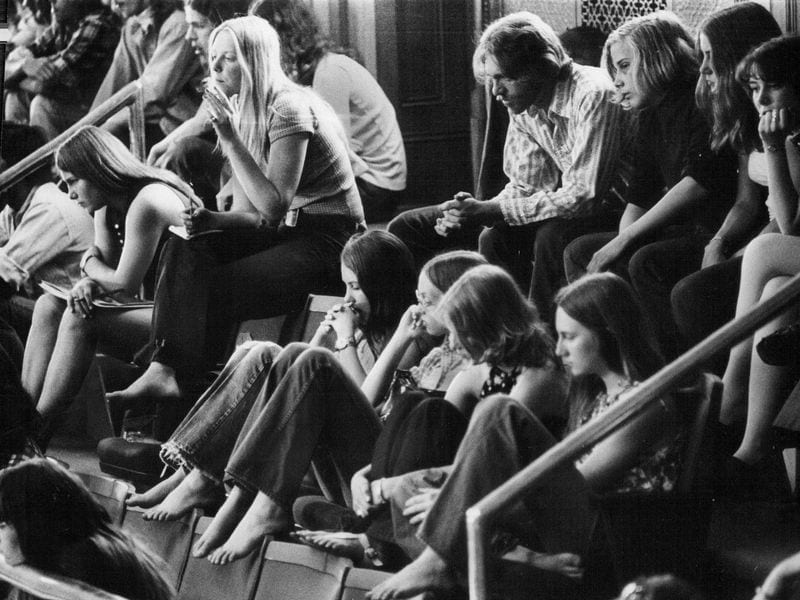

That booming paraphernalia market, however, would also prove to be decriminalization’s undoing. By 1978, rates of adolescent marijuana use had skyrocketed, with 1 in 9 high school seniors smoking pot every day and children as young as 13 reporting that the drug was “easy to get.” This angered a growing number of parents, who saw kid-oriented paraphernalia as a “gateway” to drug use. The grassroots parent movement, which began in 1976 and came to its height of influence during the Reagan administration, worked to overturn state decriminalization laws and reaffirm the federal government’s anti-marijuana stance. Once decriminalization was overturned, the paraphernalia companies that had sprouted across the country folded as quickly as they had formed.

This previous experiment with decriminalization shows exactly how shaky the current legalization efforts in the United States might actually be. Despite widespread support for legalization (including from all current 2020 candidates for the presidential Democratic nomination), an unregulated and hyper-commercialized marijuana marketplace was unpopular enough to overturn lenient drug laws 40 years ago, and could potentially do so again today.

The rise of the paraphernalia marketplace of the 1970s was grounded in two truths: America’s increasing interest in recreational marijuana use, and a struggling economy that searched for any opportunity for growth. During a period of “stagflation” and long gas lines, cannabis created its own thriving industry, from people whittling wooden pipes in their garages to major companies importing incense and beaded curtains from India. These legal products (used to enjoy a still-illegal substance) were freely available, in places like head shops, record stores, even 7-Elevens. They also sold extremely well: by 1977, paraphernalia was bringing in $250 million annually. (That amounts to over a billion dollars today.)

A blatant rush to profit today, similar to the paraphernalia market of the 1970s, could overturn the progress made by countless legalization activists over the past 20 years. Unless the market chooses to self-regulate, another graduate student might be at the Library of Congress in 40 years, wondering at how quickly and easily America’s brief experiment with legalization was overturned.